The land of the Yirrganydji people

This website acknowledges the Yirrganydji people as traditional custodians of the land at Old Smithfield township. We pay respect to their Pulpu (elders) past and present, and recognise their continuous connection to country, community and culture.

Aboriginal culture is the oldest surviving culture in the world. Aboriginal people have been in Australia, practising their culture, language and religion for 65,000 years.1

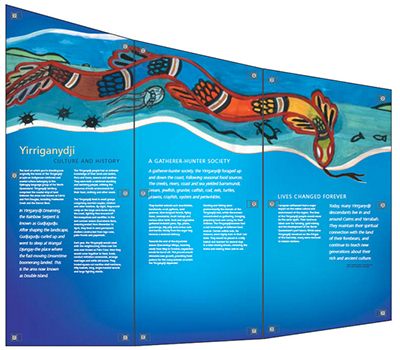

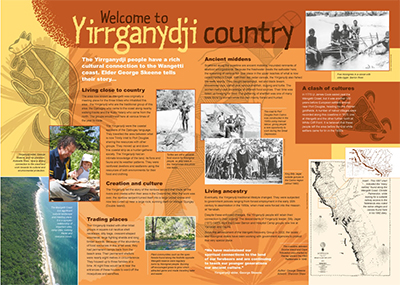

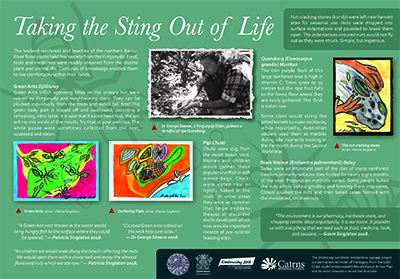

The Yirrganydji people are an indigenous Australian people and are the original custodians of a coastal strip of land within Djabugay country that runs northwards from Pana Wangal (Trinity Inlet at Cairns) to Diju (Port Douglas). Their traditional lifestyle was gatherer/hunters and fishers along the coastal rainforest, along the beaches, the river mouths, islands and seas from Bana Bidagarra (the Barron River) and northwards to Diju.

Five Aborigines in a side-rigger canoe on the Barron River, 1890s.

Eric Mjöberg, Amongst Stone Age People in the Queensland Wilderness (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Forlag, 1915), 485.

Language

The Yirrganydji pama kulpul-parra (salt-water people) spoke Yirrgay, one of five dialects of the Djabugay language. Yirrgay was the southernmost dialect of the group, with the others being Guluy, Ngakali, Djabugay and Bulway. To the south around Gimuy (Cairns) were their immediate neighbours, the Yidinji people.

Country

Yirrganydji country is the narrow coastal strip from Cairns to the Mowbray River at Port Douglas. Their country extends 12 kilometres inland around Mount Whitfield and Freshwater Creek, to the tidal waters of the Barron River at Kurra: pulay (Kamerunga). Old Smithfield township was in Yirrganydji country.

History

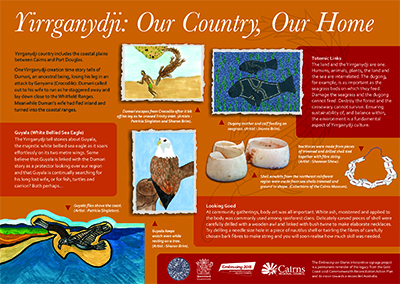

Yirrganydji creation stories tell of the travels of the Kurra kurra (ancestors): Kuju Kuju, the rainbow serpent; Puda: ji the Scrub Python; and the two brothers, Kuya: la and Dama: rri. They travelled through Yirrganydji country "and sang this land and seascape into being, shaping the mountains, rivers, islands, cays, reefs and the animals found along the coast". They gave Yirrganydji people their lore and customs, they fished, gathered and harvested minya ma:-jada (food) for ceremony and survival.2

Kuju Kuju created the rivers and creeks and then curled up in the sun next to a large rock on Wangal Djungay (Double Island at Jakal / Palm Cove). Wangal Djungay is the place where the fast-moving Storytime boomerang landed, and it also has connections to the creation stories of Puda:ji.

There are many other Yirrganydji Bulurru Storywaters, including ones explaining how Ganyarra the crocodile got his teeth, and then how he attacked Dama:rri near the mouth of Bana Bidagarra ('the river where bark canoes are used' - the Barron River). Dama:rri lost a leg in the attack and staggered to Mount Whitfield, where he lay down. His wife lay down near him and became Bunda Bunda:rra, the home of the cassowary (the Macalister Range). His brother Kuya: la became the White-Bellied Sea-Eagle, and today can be seen soaring effortlessly along the Wangka: rri (Wangetti) Coast, watching over and protecting Yirrganydji country.

European Settlement

The arrival of the gadja (white people) decimated the traditional Yirrganydji lifestyle and the Yirrganydji environment. The first reports from European observers noted the Yirrganydji had good access to the necessaries of life and that food was abundant. Sub-Inspector Johnstone of the Queensland Native Police wrote:

... it is a sure indication of good country when the aboriginals [sic] are numerous, as they depend entirely on Nature to provide them with the necessaries of life, and there in the valley of the Barron River, the jungle supplied them with fruits, roots and game in abundance.3

This recognition of traditional indigenous lifestyle did not stop Johnstone from opening fire on the Yirrganydji at their first meeting. Upon landing at Jakal (Palm Cove) in October 1873 "a considerable mob of blacks came out of their camps and in a most daring manner tried to prevent Mr. Johnstone's advance". When the warriors had approached to within 30 yards, Johnstone ordered his native police troopers to open fire with their snider rifles. According to the expedition leader, George Dalrymple, the Yirrganydji men were "severely wounded".4

Three years later, the arrival of thousands of miners at the Hodgkinson goldfield meant Yirrganydji land was appropriated for settlements like Old Smithfield township, Cairns and Port Douglas, as well as for farming and timber extraction. Yirrganydji people were displaced from their traditional country - some remained on the fringes of Cairns and Port Douglas, some were forced into unpaid employment, and many were rounded up and forcibly relocated to Mission Stations on Djabugay country at Mona Mona or Yidinyi country at Yarrabah.

In 1904 eminent German anthropologist, Prof Hermann Klaatsch visited Cairns and collected Yirrganydji artefacts from the lower Barron River. Those artefacts are now in the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum of Ethnology in Cologne.5

Yirrganydji artefacts collected on the lower Barron River in 1905.

Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum of Ethnology, Koln, Germany.

Image B5562, © George Skene

King Billy Jagar of the Barron River

Yirrganydji elder, Billy Jagar (1870-1930), was given two King-plates to recognise his leadership. The first one was presented to him by the Queensland government in 1898 and proclaimed him ‘King of Barron’. The second plate was presented by the Protector of Aborigines on Empire Day, 24 May 1906.

Jagar died in a fringe camp in Cairns in 1930 and the King-plates disappeared. During WWII the 1898 plate was acquired by US Staff-Sergeant Douglas Campbell while he was stationed in Fiji. Campbell took it home to North Dakota and hung on the wall in his living room. After Campbell’s death, his daughters Margaret and Laura investigated the origins of the plate. On Reconciliation Day, May 2005, they returned it to Cairns. The plate was presented to Jagar’s great-grand daughter, Jeanette Singleton. In 2007 a headstone for Jagar was placed at Martyn Street Cemetery.

Billy Jagar, Yirrganydji elder, King of Barron.

Yirrganydji people today

The Yirrganydji Gurabana Aboriginal Corporation and the Dawul Wuru Aboriginal Corporation published a 'Strategic Plan 2016-2021', signed the 'Yirrganydji Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreement (TUMRA)' in 2014, operate a Yirrganydji Land and Sea Ranger Program, an Estuarine Crocodile Monitoring Program and the Regional Indigenous Fashion and Textiles Showcase (RIFTS).

http://dawulwuru.com.au

The Cairns Museum has an interpretive display and artefacts explaining Yirrganydji life.

https://www.cairnsmuseum.org.au/

Yirrganydji interpretive signs have been erected by Cairns Regional Council on the Esplanade in Cairns, at Smithfield, Machans Beach, Trinity Beach and Palm Cove. the Wet Tropics Management Authority have erected a sign at Wangetti Beach.

https://www.cairns.qld.gov.au/region/heritage/culture-history

http://www.wettropics.gov.au/fromtheheart/17-my-yirrganydji-story.html

https://www.cairnsartsandculturemap.com.au/

https://www.cairnsartsandculturemap.com.au/

https://www.cairnsartsandculturemap.com.au/

https://www.cairnsartsandculturemap.com.au/

| Go to the next section ⇒ The Hodgkinson gold rush, 1876. | |

|

This webpage is an excerpt from the upcoming book Old Smithfield: Barron River township (1876-1879) by Dr Dave Phoenix. Find Out More Here |

Featured Artefacts from Old Smithfield:

-

1. Clarkson, C., Jacobs, Z., Marwick, B. et al. 'Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago' Nature 547, (2017): 306–310. ↩

-

2. Yirrganydji Kulpul-Wu Mamingal: Looking after Yirrganydji Sea Country - Yirrganydji Sea Country Plan (Cairns: Dawul Wuru Aboriginal Corporation, 2014). ↩

-

3. Robert Arthur Johnstone, Spinifex and wattle : reminiscences of pioneering in North Queensland (Brisbane: Queenslander, 1903-1905). ↩

-

4. George Elphinstone Dalrymple, Narrative and reports of the Queensland North-East coast expedition, 1873 (Brisbane, Queensland Parliament 1874): 18-19. ↩

-

5. Corinna Erckenbrecht, Maureen Fuary, Shelley Greer, Rosita Henry, Russell McGregor & Michael Wood, 'Artefacts and collectors in the tropics of North Queensland' The Australian Journal of Anthropology 21, 3 (December 2010): 350-366. ↩